Galàpagos retrospective 1985/2022

- Claudio Carabelli

- Apr 2, 2022

- 7 min read

Having noted the global climate and environmental degradation, we can ask ourselves: how long will it be possible to guarantee biodiversity and ecological processes in the Galàpagos Islands?

What has been done for their conservation? What are the main threats? And what can be done in the future to achieve the Archipelago's conservation objectives?

Galàpagos is a special name. Pronounced or heard, it evokes something romantic, exotic, magical.

For the pirates, buccaneers, whalers and adventurers of past centuries the islands were Encantadas.

They were so for its desolate areas, its landscapes of sea and sky, its active volcanoes, its peculiar flora and fauna, for the humid mist or garùa that comes from the sea carried by the wind from the south-east.

The existence of the Galàpagos attracted the attention of many naturalists, such as Charles Darwin who founded the Theory of the Evolution of Species mainly on the basis of his observations made during five weeks of presence in the Archipelago, revolutionizing the biological scientific thought of his time. that in trying to explain the great variety of living species, he was unable to go beyond the millennial creationism.

Geology of the Archipelago

The Archipelago, located on the Equator about 1000 km from the coast of Ecuador, is made up of 13 main islands, 6 small islands, 42 islets and many more or less large rocks, which together cover a total surface area of about 8 thousand. sq. km.

The islands are the product of hot spots, areas of the earth's crust affected by the upwelling of basaltic magma from the deep part of the mantle.

They are located on the Nazca plate but very close to the diverging edge of the Cocos plate and the Pacifica plate. When the magma rises to the surface it is subjected to plate drift: since the movement is directed towards the South American coast, the westernmost islands are also the oldest.

The Galàpagos hot spot is about 20 million years old, the oldest islands were formed about 5 million years ago, the last about 1 million years ago.

From Milan Malpensa to Baltra

Upon arrival at Baltra airport a bus takes us to the Canal de Itabaca which we cross with a small ferry that transfers us to the island of Santa Cruz.

It is the first contact with the Galàpagos islands. We cross the interior of the whole island to reach Puerto Ayora, where we will stay for about ten days and where the Charles Darwin Foundation is based.

Endemic botany: no relationship with Mexican and Central American flora

Along the path that leads us to Puerto Ayora we encounter an arid zone vegetation: the most common endemic species are Jasminocereus thouarsii, a cactus with a single species and the gigantic Opuntia echios.

99% of the islands' non-endemic vascular plants come from South America and only 1% from Mexico.

The seeds were carried by wind, birds and ocean currents.

Other endemic species form wooded shrub areas of Scalesia pedunculata and Miconia robinsoniana: these species, especially the latter which regenerates slowly, are threatened by the presence of mammals introduced by man.

In the coastal strip, especially in the tidal area, located in the few estuaries, bays and inlets, expanses of mangroves can be observed.

Puerto Ayora: yesterday (1985) and today (2022), crowded with boats

A few thousand tourists a year in the 1980s, 250,000 today!

Ferries, yachts, yachts, sailboats that transport tourists to the islands create noise and damage to the marine ecosystem.

It is now clear to everyone that, beyond the policy of "open skies" desired by the government of Ecuador, it is necessary to restrict tourist flows.

The Archipelago has been a National Park of Ecuador since 1959 (one hundred years after the publication of the Origin) and in 1964 the Charles Darwin scientific station was founded, whose primary objective was precisely the conservation of the Galápagos, undertaking programs that also included the elimination from the island of animal and plant species introduced by man.

The station is also renowned for captive breeding of giant tortoises.

Yesterday (1985) and today (2022)

Oceanography: the terrifying el Niño

The Archipelago is located at the confluence of three ocean currents: the von Humbolt current, a cold current (15 °) that skirts and goes up the coast of Chile and Peru, very rich in plankton, the Cromwell current, deep and cold (-200 m 13 °), and the warm Panama current, which descends from the tropic.

When Humboldt and Panama reach the Equator and therefore the Galàpagos, they veer westward.

For this reason, the southern front of the Archipelago is lapped by colder waters that allow the life of colonies of penguins, while the northern front has warmer waters.

Plankton represents the first step of the food pyramid, with crustaceans, fish and birds superimposed on it.

But every 2-7 years the temperature of Panama changes: starting from the Christmas period el Niño flows, a very complex oceanic phenomenon.

This occasional appearance of hot water, probably caused, but not only by the appearance of the trade winds, sometimes leads to an excessive rise in temperature: even 4/5 degrees more.

When el Niño reaches 20 ° / 21 ° it is the cause of a natural catastrophe: cold water goes deep, dragging plankton and fish and consequently coastal birds die in large quantities, not having sufficient food reserves.

Yesterday (1985) and today (2022)

With a boat we reach a small island north of Santa Cruz: San Bartolomé; it is an evocative island. A postcard view is offered to us after the short climb to the crater of the volcano.

In the following days we move between other islands, Santa Fé, Dafne, Pinzon, to meet a colony of penguins, various birds and sea lions (Lobos de mar).

Reptiles: when evolution gets busy

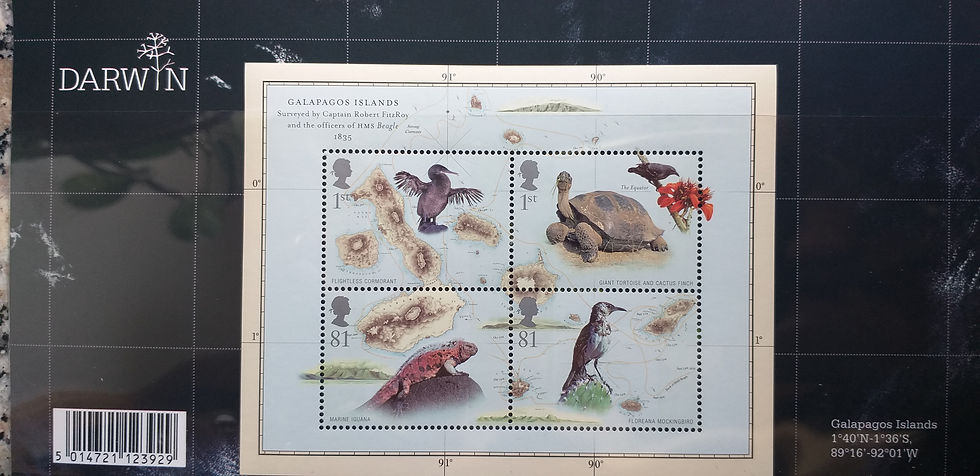

While terrestrial iguanas are widespread almost everywhere, marine iguanas, Amblyrhynchus cristatus, are endemic to the Galàpagos.

They derive from the terrestrial ones and represent a form of marine alimentary adaptation: they feed on algae, swimming slowly and remaining in water for not long, as the body heat, up to 40 °, absorbed during exposure to the sun, is dispersed in water quickly.

They are darker and smaller in size than terrestrial ones.

They spend most of their time ashore, on rocky lava.

Yesterday (1985) and today (2022)

The giant tortoises of the Galàpagos, Geochelone elephantopus, are represented by 11 races: their variability, in particular as regards the saddle, depends on the environmental conditions of the islands in which they live and reproduce.

Over time, the giant tortoises have fallen prey to humans and mammals introduced by them.

But it was also understood that by intervening by protecting them from natural predators and by incubating the eggs, therefore with minimal effort, it is possible to increase the fertility rate of the colonies.

The birdlife of the Galàpagos

There are 57 different species of birds known, of which 28 are endemic.

A large number of tree species is the main factor affecting the number of land bird species.

There are: Spheniscus mendiculus (G. penguin), Diomedea irrorata (Albatro de G.), Sula nebouxii (Piquero patas azules), Nannopterum harrisi (Cormorano de G.), Fregata magnificens (Royal frigate) and Fregata minor, Camarynchus heliobates (G. chaffinch).

If the number of birds is regulated by the availability of food, as suggested by the evidence, the species living on the same island and area resort to different factors to reduce intraspecific competition for food: they feed in different places, at times different, in different ways.

The famous finches studied by Darwin belong to the Geospizinae group of the Galàpagos, represented by 14 species: a real adaptive radiation on different islands.

Frigate, Blue-footed Booby, Pinzòn (Chaffinch) de Manglar

In defense of a unique biodiversity

Chapter XVII of a Naturalist's Journey Around the World, dedicated to visiting the Archipelago, is concluded by Charles Darwin as follows:

"... from these facts we can deduce what a massacre the introduction of some new animal of robbery must cause in a region, before the instincts of its indigenous inhabitants have adapted to the strength and power of the foreigner".

Active research projects in the Galàpagos

There are 16 current projects that aim to safeguard the biodiversity of the Islas.

Here are the main ones:

The main objective of this project is to learn about the movement patterns of Galàpagos turtles and the social, ecological and health factors that influence their conservation.

Invasive plant mapping

The main objective is to have maps of the distribution and abundance of invasive plant species to support conservation efforts in the Galàpagos.

The main objective of the program is to minimize the negative impacts of invasive species on marine biodiversity, ecosystem services and the health of the Galàpagos Marine Reserve.

The Galàpagos penguin, the cormorant no volador and the Galàpagos albatross are endemic bird species.

The main objective of this project is to generate information to know the state of the population (survival) and determine space-time changes, identify threats (introduced species and pathogens) and know the impact of climate and oceanographic variability on colonies. breeding, which will serve to improve the long-term species management plan.

This species, one of Darwin's fourteen species of finches, has a population of only about one hundred, distributed over a few hectares on Isabela Island. It is at high risk of extinction.

The main objective is to improve the population status of the mangrove finch in its natural habitat through intensive management of in situ conservation.

Twenty bird species including twelve finches are victims of this imported fly on the island.

It identifies the nests and deposits its eggs there. When the larvae are born, they feed on the blood of the birds' offspring and cause their death.

The main objective is to develop effective tools for the management of Philornis downsi and to ensure the long - term conservation of the land birds of the Galàpagos.

"Among the damage from global warming, illegal fishing and the arrival of intrusive human-related species (such as goats, dogs, cats and mice brought from the mainland), having to face hordes of tourists for the delicate balance of the 138,000 square kilometers of marine reserve would be really too much ".

Giacomo Taglinani, The Republic

Bibliography

Compendium of Ciencia en Galàpagos 1982 Publicacion de la Estacion cientifica "Charles Darwin"

Origin of the species by natural choice Charles Darwin (trad. Prof. Giovanni Canestrini) 1875 Unione Tipografico Editrice Torinese

Journey of a naturalist around the world Charles Darwin (trad. Prof. Michele Lessona) 1873 Unione Tipografico Editrice Torinese

Comments